COVID-19を引き起こす新型コロナウイルスSARS-CoV-2は、中国の武漢の生物学研究所で作られてそれが外に漏れたのではないかと、当初言われていましたがなんとなく立ち消えになっていたように自分は思っていました。普段、出まかせでいい加減なことしか言わない米国のトランプ大統領が新型コロナウイルスは中国の研究所が起源だといったところで、また何の根拠もないことを言ってる、くらいにしか思っていませんでした。しかし、実はあまり大々的に報道されていなかっただけで、確固たる証拠(研究計画書)が出ていたんですね。下のツイートを見るまで自分は知りませんでしたが、2021年9月に明らかになっていたことでした(DRASTIC – An Analysis of Project DEFUSE September 2021, Leaked Grant Proposal Details High-Risk Coronavirus Research September 23 2021 The Intercept)。新型コロナウイルスのゲノムの構造は、2018年にアメリカDARPAの研究費助成事業に応募するためにEco Health Allianceniiによって提出された研究計画書(PIはPeter Daszak博士で、武漢のウイルス研究所の石 正麗(Zheng-Li Shi)博士との共同研究)における設計方針と一致しており、人工的に構成されたものである可能性が高いというものです。

エプスタイン文書の公開により、これまで陰謀論として片付けられてきたことが、人々の想像力をはるかに超えた現実であったことが明らかになった結果、既にニュースなどで報道されて知っていたはずの事を受け止める感覚が変容したように思います。

エプスタイン文書の公開で、今まで新型コロナウイルス人工説を陰謀論扱いしてきた人も、考えを変え始めているようです。COVID研究所起源説には科学的に明確な根拠があります。この機会にぜひ解説動画をご覧いただき、「不都合な真実」に向き合っていただければと存じます。https://t.co/edL1GtYhCU

— Hideki Kakeya, Dr.Eng. (@hkakeya) February 4, 2026

この文書「DRASTIC – An Analysis of Project DEFUSE」について解説した動画:

Odds Increase that SARS CoV 2 was Lab Made Age case V

AIにもざっくりとまとめてもらいました。

ーーー以下、Geminiによるまとめーーー

DEFUSE計画の原文(DRASTIC等の分析を含む)および関連する米議会調査資料を網整理します。

DEFUSE計画(2018年提案)の概要

DEFUSE計画(Project DEFUSE: Defusing the Threat of Bat-borne Bat-related Coronaviruses)は、EcoHealth Alliance(EHA)が中心となり、武漢ウイルス研究所(WIV)やノースカロライナ大学(UNC)らと共同で、DARPA(米国国防高等研究計画局)へ提出した研究提案です。

1. ヒト受容体(ACE2)結合能の改変とキメラ構築

計画では、野外で収集したSARS関連コロナウイルス(SARSr-CoV)をそのまま研究するのではなく、分子生物学的手法を用いたゲノム改変が記されていました。

-

スパイクの置換と合成: ヒト細胞への感染能を評価するため、野生型ウイルスのスパイクタンパク質を、ヒトのACE2受容体に対する親和性が高いことが判明しているスパイク、あるいは計算科学的に設計された「合成スパイク」と入れ替える実験。

-

バックボーン(骨格)への導入: 合成または選択したスパイクのDNA配列を、既知のSARSr-CoV(例: WIV1など)の全長ゲノムクローン(バックボーン)に挿入。これにより、「体は既存のウイルスだが、鍵(スパイク)だけが強力な人造キメラウイルス」を作成する。

-

目的: 本来はヒトへの病原性が低い、あるいは不明なコウモリウイルスが、「スパイクの数アミノ酸の変異」だけでパンデミックを引き起こす潜在能力(Spillover potential)を持つかを定量化するため。

2. フーリン切断部位(FCS)の導入とその機能

計画書において最も論争を呼んでいるのが、フーリン切断部位(Furin Cleavage Site: FCS)の挿入計画です。

-

具体的な操作: SARSr-CoVのスパイクタンパク質にあるS1/S2境界部位に、適切なプロテアーゼ切断部位(フーリン配列)が存在しない場合、そこに特定の配列を人為的に導入する。

-

働き:

-

膜融合の促進: フーリンはヒトの細胞内に広く存在するタンパク質分解酵素です。ウイルスが細胞に吸着した際、フーリンによってスパイクが効率的に切断(プライミング)されることで、ウイルスのエンベロープと宿主細胞膜の融合が劇的にスムーズになります。

-

感染力と組織指向性の拡大: これにより、呼吸器系だけでなく全身の様々な細胞への感染が可能になり、結果として病原性と伝播力を著しく高める働きをします。

-

計画書には「S1/S2境界へのヒト特異的な切断部位の導入」が、実験のステップとして記載されていました。

3. リスクの高い実験と不適切なBSL施設

この計画には、バイオセーフティ(安全管理)に関する重大な「過失」または「意図的な過小評価」が含まれていました。

-

BSL-2での実施計画: 計画の草案や内部メールから、これらの高度な感染性クローン作成および機能獲得実験の多くを、武漢ウイルス研究所のBSL-2(バイオセーフティレベル2)施設で実施する予定であったことが判明しています。

-

リスクのミスマッチ: SARS関連ウイルスの機能獲得研究(GoF)は、通常BSL-3以上、あるいはBSL-4での実施が国際的な常識です。BSL-2は一般的な病原体を扱うレベルであり、エアロゾル対策などが不十分です。

-

隠蔽の意図: 内部文書(DRASTIC報告等)によれば、PIのダスザック氏は「アメリカの審査を通しやすくするために、高度な実験はノースカロライナ大学(BSL-3以上)でやると見せかけ、実際には低コストで規制の緩い武漢(BSL-2)で実施する」という二重構造の戦略を練っていた形跡が指摘されています。

4. 野外での先制攻撃(エアロゾル散布)

研究室内の実験に留まらず、野外でのリスクを伴う提案も含まれていました。

-

洞窟への散布: 開発した免疫増強剤やワクチン成分を、自動噴霧装置を用いて中国雲南省のコウモリの洞窟に直接エアロゾル散布する計画。

-

懸念: これにより、自然界でのウイルスの変異を加速させたり、予期せぬ流出を引き起こしたりするリスク(ELSIおよびDURCの懸念)が考慮されていませんでした。

この計画は、「自然界に存在する脅威を予測する」という大義名分の下で、「DNA合成とリバースジェネティクスを用いて、意図的に感染力と病原性を高めたウイルス(FCS挿入キメラ)を設計し、それを不十分な安全基準(BSL-2)の下で大量に作成・試験する」という、科学倫理および安全保障上の致命的な欠陥を抱えたものであったということが公開された文書から読み取れます。

ーーー以上、Geminiによるまとめーーー

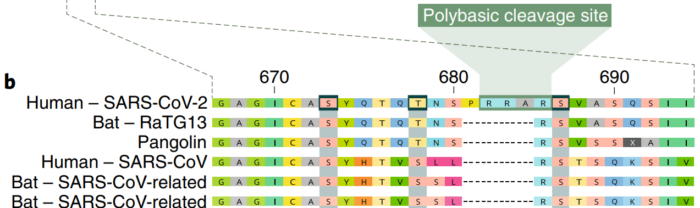

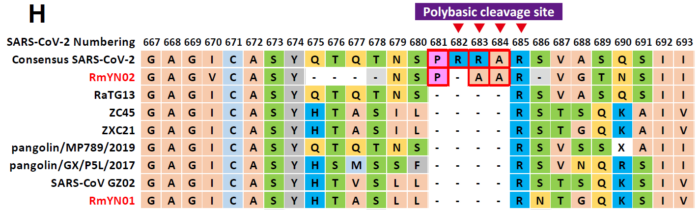

フーリン切断部位(Furin Cleavage Site: FCS)

新型コロナウイルスのゲノムを解析した論文に、酵素フーリンによる切断の際の認識部位(RRAR)の図があります。この図で明らかなように、近縁ウイルスの間にはRRARの配列はありませんが、なぜかHuman-SARS-CoV-2にだけPRRA(プロリン、アルギニン、アルギニン、アラニン)というアミノ酸配列が挿入されており、RRARという配列を持つことになります。この図の論文は、研究所起源説を否定する主張をする論文ですが、自然な変異でちょうどスパイクタンパク質のS1サブユニットとS2サブユニットのちょうど境界にPRRAという配列が挿入されるというのは非常に考えにくいことであり、研究者が人工的に挿入した結果と考えるほうが、現実的にありそうなことに思えます。実際に、武漢の研究者がそのような研究計画書を新型コロナウイルスパンデミックが起こる前にアメリカのDARPAに提出していたという事実は、この人造ウイルス仮説を強力に支持します。

Andersen et al. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med 26, 450–452 (2020) Fig.1

SARS-CoV-2が人工的に合成されたことを示唆する痕跡

概要 天然のコロナウイルスを模した合成ウイルスを研究室で作製する際、研究者はしばしば「in vitro(試験管内)ゲノムアセンブリ」という手法を用います。この手法では、「制限酵素」という特殊な酵素を使い、ウイルスのゲノムを正しい順序で「縫い合わせる」ためのDNAの構成ブロックを作成します。 研究室でウイルスを合成する場合、通常はゲノムを操作して、この縫い合わせ場所となる「制限部位」を追加したり削除したりします。こうした部位の改変の仕方は、試験管内でゲノムが組み立てられたことを示す「指紋(証拠)」として機能します。 私たちの研究により、SARS-CoV-2には合成ウイルス特有の制限部位の「指紋」があることが判明しました。SARS-CoV-2に見られるこの合成の指紋は、野生のコロナウイルスにおいては異例であり、研究室で組み立てられたウイルスにおいては一般的です。 SARS-CoV-2の制限部位を区別している変異の種類(同義置換またはサイレント変異)は、遺伝子工学的な操作に特有のものです。また、制限部位にこれらのサイレント変異が集中している確率は、ランダムな進化によって生じるには極めて低いものです。 制限部位の「指紋」と、それを生じさせた変異パターンの両方が、野生のコロナウイルスでは極めて稀であり、合成ウイルスではほぼ普遍的に見られます。以上の知見は、SARS-CoV-2が合成由来である可能性を強く示唆しています。

結論 SARS-CoV-2におけるBsaIおよびBsmBI(制限酵素)のマップは、野生のコロナウイルスとしては異常であり、効率的なリバースジェネティクス(逆遺伝学)システムとして設計された「感染性クローン」に由来する可能性が高い。

(Endonuclease fingerprint indicates a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2 Valentin Bruttel, Alex Washburne, Antonius VanDongen bioRxiv 2022.10.18.512756; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.18.512756 PDF Gemini3による訳)

ヒトへの感染能と病原性を高めるような改変を行って、未知の危険なウイルスを作り上げておきながら、それを既知の危険性が低いウイルスをあつかうBSL2の施設で実験していたら、何が起こるか誰でも想像がつくのではないのでしょうか。素人ならまだしもウイルス学を専門とする研究者が杜撰なやり方で研究を実施した結果、地球上の500万人以上の命を奪ったのだとしたら、本当に恐ろしい話です。正直言って、実感を伴いません。

DFUSE計画申請書がアップロードされているサイト

- https://ermsta.com/r/defuse_grant.pdf

- https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21066966-defuse-proposal/

リジェクトの通知

- The proposal is considered to potentially involve GoF/DURC research because they propose to synthesize spike glycoproteins which bind to human cell receptors and insert them into SARSr-CoV backbones to assess whether they can cause SARS-like disease.

- However the proposal does not mention or assess potential risks of Gain of Function (GoF) research.

- (以下略)

REJECTION OF DEFUSE PROJECT PROPOSAL Proposal Title: Proposal Identifier: DEFUSE – Defusing the Threat of Bat-borne Coronaviruses (2018)https://assets.ctfassets.net/syq3snmxclc9/5OjsrkkXHfuHps6Lek1MO0/5e7a0d86d5d67e8d153555400d9dcd17/defuse-project-rejection-by-darpa.pdf

申請書の内容に関する分析

- An Analysis of the Project DEFUSE proposal submitted by EcoHealth Alliance [EHA] to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency [DARPA] on 3/27/2018 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363729325_DRASTIC_-_An_Analysis_of_Project_DEFUSE

PIに対する責任の追及

どうやら、このPIは、アメリカの予算を獲得しやすいように(BSLが高い)アメリカの大学の研究所で研究実施をするといいつつ、実際には(危険なウイルス実験をやるにはBSLが高くない)中国の武漢でやるつもりだったようです。

We write to urge the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) immediately to suspend Dr. Peter Daszak’s status and affiliation with NAM1 and to proceed with an investigation into his conduct in connection with a grant awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to Dr. Daszak as the Principal Investigator (PI) for EcoHealth Alliance (EcoHealth) and a subgrant recipient, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), to determine whether his actions constitute violations of NAM’s Code of Conduct that warrant expulsion.

November 30, 2021 https://d1dth6e84htgma.cloudfront.net/legacy/uploads/2021/11/2021.11.30-NAM-Daszak-Letter.pdf

Since the beginning of the 118th Congress, the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic and the Committee on Energy and Commerce (together “the Committees”) have been investigating the origins of COVID-19 and related issues.

We look forward to your testimony at a public hearing on May 1, 2024. In accordance with all applicable rules, a formal invitation will follow.

Findings from EHA documents made public by Congress in December 2024

Version 1.2.1—Sep 2025 Authors: G. Demaneuf, B. Bosti https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gilles-Demaneuf/publication/395016679_Findings_from_EHA_documents_made_public_by_Congress_in_December_2024_-DRASTIC_Working_Notes_-_PREVIEW_LINKS_REMOVED/links/68c3ac496f596e0b91a5ed65/Findings-from-EHA-documents-made-public-by-Congress-in-December-2024-DRASTIC-Working-Notes-PREVIEW-LINKS-REMOVED.pdf

参考

- Unusual Features of the SARS-CoV-2 Genome Suggesting Sophisticated Laboratory Modification Rather Than Natural Evolution and Delineation of Its Probable Synthetic Route https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Limeng-Yan/publication/344240007_Unusual_Features_of_the_SARS-CoV-2_Genome_Suggesting_Sophisticated_Laboratory_Modification_Rather_Than_Natural_Evolution_and_Delineation_of_Its_Probable_Synthetic_Route/links/610776dd169a1a0103cf7ecb/Unusual-Features-of-the-SARS-CoV-2-Genome-Suggesting-Sophisticated-Laboratory-Modification-Rather-Than-Natural-Evolution-and-Delineation-of-Its-Probable-Synthetic-Route.pdf

- SARS-CoV-2 Is an Unrestricted Bioweapon: A Truth Revealed through Uncovering a Large-Scale, Organized Scientific Fraud https://www.queendairy.com/files/pdf/The_2nd_Yan_Report.pdf

- COVID-19 lab leak theory https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_lab_leak_theory

ウェブ記事、報道など

- Defense Intelligence Agency considered lab leak scenario in March 2020, new records show Lewis Kamb | February 5, 2026

- WHO says all COVID-19 origin theories still open, after inconclusive study Jun 28, 2025 The Japan Times All hypotheses on how the COVID-19 pandemic began remain open, the World Health Organization said Friday, following an inconclusive four-year investigation that was hamstrung by crucial information being withheld.

- 米ホワイトハウス、新型コロナの特設ページ開設 武漢の研究所から「流出」 2025.04.20 CNN ウイルスが「自然界には見られない生物学的特性」を持ってい

- 「新型コロナは武漢研究所から流出」 米ホワイトハウスが特設サイト 2025年04月19日 時事

- 米ホワイトハウス、「新型コロナ起源は中国・武漢の研究所」とする特設サイト立ち上げ テレ東BIZ ダイジェスト チャンネル登録者数 254万人 2025/04/19

- 新型コロナウイルス、中国・武漢の研究所から流出可能性「80~95%」…ドイツ情報機関が極秘報告書 2025/03/13 19:14 読売新聞オンライン 独連邦情報局(BND)は、19、20年に執筆された新型コロナウイルスに関する未発表論文などを入手して分析。報告書では、武漢のウイルス研究所が、人間に感染しやすいようウイルスを改変する実験を行っていたと指摘した。ウイルスの扱いはずさんで、多くの安全規則違反があった

- 新型コロナ、自然界発生より研究所から流出した可能性高い=CIA Erin Banco 2025年1月28日午前 7:49 GMT+9 Reuters ウィリアム・バーンズ前長官がバイデン前政権末期の数週間にCIAのアナリストと科学者らにパンデミックが起きたことの歴史的重要性を強調し、明確な判断を下すよう求めた

- コロナ起源でCIAの見解変化-研究所流出の可能性「より高い」 2025年1月27日 Boomberg

- コロナ起源は「中国研究所の事故」 米下院小委が報告書 2024年12月5日 7:14 日本経済新聞 2019年秋に複数の研究所の職員が新型コロナに似たような症状が出ていた 米疾病対策センター(CDC)や米国立アレルギー感染症研究所(NIAID)は動物を介して人間に感染した可能性が高いとみている。だが、米連邦捜査局(FBI)と米エネルギー省は研究所から流出した可能性が高いと判断している。

- COVID-19 cover-up claims swirl after whistleblower reveals disease ‘blueprint’ may have been wrongly classified By Josh Christenson and Caitlin Doornbos Published Nov. 14, 2024, 3:10 p.m. ET NEW YORK POST DEFUSE提案書は、その後科学者たちによって「新型コロナが中国の研究所で操作されたことを示す『決定的な証拠(スモーキング・ガン)』」として引用されているが、――非機密文書であったにもかかわらず――2021年8月に発表された国家情報長官室(ODNI)によるウイルス起源に関する最終報告書には含まれていなかった。

- 米有力紙が「コロナ人工説」を報道 研究所流出説は常識化し、いよいよ核心である人工説に踏み込み始めた 2024.03.01 The Liberty Web

- S.Hrg. 118-355 — ORIGINS OF COVID-19: AN EXAMINATION OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE https://www.congress.gov/event/118th-congress/senate-event/LC73181/text

- Wuhan Institute may not have had the required safety level for virus research, specialist says 05 Mar 2023 04:03:14 GMT9

- 新型コロナ感染症の起源は武漢市場のタヌキか? 2023/4/4 東京都医学総合研究所

- FBI長官が新型コロナウイルスの起源に言及 2023/3/14 東京都医学総合研究所 ワシントンポスト紙に掲載された社説(文献1)を和訳して報告 文献1.

What we know about the origin of covid-19, and what remains a mystery

By Joel Achenbach, The Washington Post. Published February 28, 2023 at 11:15 a.m. EST - The possible lab-leak origin of SARS-CoV-2: why is an inquiry into this matter so critical? April 2023 DOI:10.22541/essoar.168167208.89643008/v1 Antonio Fábio Medrado de Araújo Federal University of Bahia Liliane Lins-Kusterer Federal University of Bahia Eduardo Martins Netto Federal University of Bahia https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370066237_The_possible_lab-leak_origin_of_SARS-CoV-2_why_is_an_inquiry_into_this_matter_so_critical

- 新型コロナの中国研究所流出説、なぜ論争が続くのか 2023年3月3日 BBC NEWS 米連邦捜査局(FBI)のクリストファー・レイ長官は2月28日、新型ウイルスが「中国政府が管理する研究所」から発生した可能性が「最も高い」と発言 研究所流出説はかつて、根拠薄弱な陰謀説とも言われていた 武漢ウイルス研究所(WIV)は10年以上、コウモリを宿主とするコロナウイルスを研究していた 研究所流出説を採る人の間では、研究所から漏れた新型ウイルスは同研究所で人工的に改変されたのではなく、野生動物から採取されたままのものだろうという見方が優勢

- コロナ起源「研究所流出説は少数意見」米CNN 情報機関で違う見解 有料記事 ワシントン=合田禄2023年2月28日 13時30分 朝日新聞

- An Analysis of the Origins of the COVID-19 Pandemic Interim Report Senate Committee on Health Education, Labor and Pensions Minority Oversight Staff October 2022 https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/report_an_analysis_of_the_origins_of_covid-19_102722.pdf

- 新型コロナ、「米中合作」の可能性浮上…米国、武漢研究所のコロナ研究に資金提供との報道 RIETI 経済産業研究所 2021年9月13日 米インターネットメディア ザ・インターセプトが「NIHが中国武漢ウイルス研究所に連邦資金を提供して、人間に感染するコウモリのコロナウイルスの研究を行っていたことがわかった」と報じた インターセプトは米情報公開法により900ページ以上にわたるNIHの未公開文書を入手 NIH助成研究タイトル「コウモリ・コロナウイルスの出現リスクに関する評価」ニューヨークの非営利団体エコヘルス・アライアンスに2014年から19年にかけて総額310万ドルの資金提供、そのうち59万9000ドルが武漢ウイルス研究所に配分 SARS系統のコロナウイルスを人間に感染しやすくする遺伝子操作を行い、その効果はヒト化マウスで確認

- Leaked Grant Proposal Details High-Risk Coronavirus Research The proposal, rejected by U.S. military research agency DARPA, describes the insertion of human-specific cleavage sites into SARS-related bat coronaviruses. Sharon Lerner, Maia Hibbett September 23 2021, 2:16 p.m. The Intercept Since the genetic code of the coronavirus that caused the pandemic was first sequenced, scientists have puzzled over the “furin cleavage site.” This strange feature on the spike protein of the virus had never been seen in SARS-related betacoronaviruses, the class to which SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes the respiratory illness Covid-19, belongs.

- DRASTIC – An Analysis of Project DEFUSE September 2021 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.12961.89442 抄録 2018年3月27日にエコヘルス・アライアンス(EHA)が国防高等研究計画局(DARPA)に提出した「DEFUSE計画」の提案書には、2019年秋に武漢で出現したSARS-CoV-2ウイルスを直接的に生み出した可能性のある実験が、極めて詳細に記述されている。特に懸念される要素としては、SARS様コロナウイルスへの「ヒト型プロテアーゼ切断部位」の導入、DC-SIGN経路を利用可能なウイルス株の特定に対する強い関心、ヒト化マウスにおけるACE2親和性をテストするための「主要なRBD(受容体結合ドメイン)残基」の導入、およびコウモリのインターフェロン応答を標的にした「ブースティング(抑制)」が挙げられる。初期の野生型SARS-CoV-2ゲノムが、フリン切断部位、高いヒトACE2親和性、DC-SIGN受容体、およびインターフェロン応答を減退させる複数のORF(オープンリーディングフレーム)構成要素を有していたことを鑑みると、DEFUSE計画の提案文書の存在は、SARS-CoV-2ウイルスおよびCOVID-19パンデミックの起源について、重要な疑問を投げかけるものである。 https://drasticresearch.org/2021/09/20/1583/

- Origins of SARS-CoV-2: window is closing for key scientific studies Authors of the March WHO report into how COVID-19 emerged warn that further delay makes crucial inquiry biologically difficult. 25 August 2021 Nature

- 新型コロナ研究所流出説、研究者生命を賭けたある科学者の闘い by Antonio Regalado2021.08.12 MIT Technology Review 5人のウイルス学者による論文『The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2(新型コロナウイルスの近位起源、以降Proximal Origin)』では研究所から流出する、すべての可能性を考慮していなかった。

- 米情報機関、武漢研究所の膨大な遺伝子データを調査 コロナ起源解明で CNN EXCLUSIVE 2021.08.06 Fri posted at 10:58 JST CNN 米政府内外の調査員は以前から、武漢ウイルス研究所で扱われていた2万2000のウイルス試料の遺伝子データを入手しようとしてきた。このデータは2019年9月に中国当局者によってインターネットから削除され、以降、中国は初期のコロナ症例に関する生データを世界保健機関(WHO)や米国に提出するのを拒んでいる。

- 単なる陰謀論ではなかった…? 武漢ウイルス研究所「流出説」を再燃させた“匿名専門家集団”の正体 近藤 奈香2021/07/21 source : 文藝春秋 2021年8月号 文春オンライン 石正麗博士はコウモリのコロナウイルスを分析し、SARSに最も似たゲノム配列を持つウイルスをRaBtCoV/4991と命名

- WHO-convened global study of origins of SARS-CoV-2: China Part Joint WHO-China study: 14 January – 10 February 2021 30 March 2021 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-convened-global-study-of-origins-of-sars-cov-2-china-part Geminiによるまとめ:この文書は、2021年に発表されたWHO(世界保健機関)と中国による合同調査報告書(いわゆるWHO報告書の正式版)です。 結論は明確に「自然流入説」を支持しており、研究所由来説をほぼ否定しています。 報告書では、ヒトへの流入経路について4つの可能性を評価し、以下のように結論づけています。 ①中間宿主を介した自然流入(Possible to Likely): コウモリから他の中間宿主(野生動物など)を介してヒトに感染した。これが「最も可能性が高い」。 ②動物からの直接的な自然流入(Possible): コウモリなどの宿主から直接ヒトに感染した。 ③冷凍食品(コールドチェーン)を介した流入(Possible): 汚染された冷凍食品を通じてウイルスが持ち込まれた(中国側が強く主張した説)。 ④研究所関連の事故(Extremely Unlikely): 研究所からの漏洩。これは「極めて可能性が低い」と一蹴。 この報告書は、発表直後から「中国側への過度な配慮」や「情報の透明性の欠如」について、米国を含む多くの国々や科学者から強い批判を浴びました。特に、研究所への立ち入り調査や生データの開示が極めて限定的だったため、後にWHOのテドロス事務局長自身も「研究所流出の可能性を排除するには時期尚早だった」と認め、再調査を求める事態となりました。 これまで議論してきたDEFUSE計画(2018年)の存在などは、このWHO報告書の段階では十分に考慮・検証されていなかった重要な「抜けているピース」の一つと言えます。

- Wuhan coronavirus hunter Shi Zhengli speaks out China’s “Bat Woman” denies responsibility for the pandemic, demands apology from Trump. 24 Jul 2020 By Jon Cohen Science

- 独占インタビュー:武漢ウイルス研究所のコロナウイルス専門家石正麗氏 2020年8月28日

- ‘Heinous!’: Coronavirus researcher shut down for Wuhan-lab link slams new funding restrictions Peter Daszak, president of the research organization EcoHealth Alliance, describes how he has been caught in political cross-hairs over his partnership with a virology lab in China. 21 August 2020 Nature

- 武漢研究所のコウモリ学者、コロナ発生源説を否定 世界的なウイルス研究者、COVID-19の世界的流行で注目の的に The Wall Street Journal 国際The Wall Street Journal発 2020年4月22日 12:07 有料会員限定 DIAMOND ONLINE

- Andersen, K.G., Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W.I. et al. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med 26, 450–452 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9 Published:

2021年9月に前述したような暴露、告発が行われていたにも関わらず、アカデミアでは人造ウイルス説を唱える声があまり聞かれなかったのも不思議です。どちらかといえば、ウイルス学者たちは一貫して自然発生説を主張する論文を出し続けてきたように思います。以下、ほぼすべてがラボ流出説を否定する論調の論文です。DARPAの計画書が明るみに出たのが2021年9月なので、それ以前の論文はこのことが考慮されていません。不可解なのは、最近の論文であっても、ラボ流出説に否定的なものが多いことです。まあ、ラボ流出説を主張すると、必然的に政治的なトラブルに巻き込まれるので、誰も公の立場では口にできないでしょう。政治とは無関係に科学者として存在することは不可能ように思います。

新型コロナの起源を推察する論文

- Domingo, J. (2025). The Contentious Origins of SARS-CoV-2: A Comprehensive Review of Current Knowledge. Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/az7d1x.5

- Afolabi, C., Adekunle, J., Oyeniran, M., Oyelakin, S., Ogu, C., Ayanlowo, E., Robert, C., Sule, H., Ideh, G., Alagbe, S., Fagbemiro, O., Adeniyi, Y., Adegboyega, T., Samsudeen, O., Badru, K., Shakioye, K., Alimi, A., Amos, A., & Ebonyem, B. (2025). COVID-19 Origins: Quantifying Scientific Consensus Amid Political Polarization Through Mixed-Methods Meta-Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.06.25328995

- Alwine, J., Goodrum, F., Banfield, B., Bloom, D., Britt, W., Broadbent, A., Campos, S., Casadevall, A., Chan, G., Cliffe, A., Dermody, T., Duprex, P., Enquist, L., Frueh, K., Geballe, A., Gaglia, M., Goldstein, S., Greninger, A., Gronvall, G., Jung, J., Kamil, J., Lakdawala, S., Liu, S., Luftig, M., Moore, J., Moscona, A., Neuman, B., Nikolich, J., O’Connor, C., Pekosz, A., Permar, S., Pfeiffer, J., Purdy, J., Rasmussen, A., Semler, B., Smith, G., Stein, D., Van Doorslaer, K., Weller, S., Whelan, S., & Yurochko, A. (2024). The harms of promoting the lab leak hypothesis for SARS-CoV-2 origins without evidence. Journal of Virology, 98. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01240-24

- Alwine, J., Casadevall, A., Enquist, L., Goodrum, F., & Imperiale, M. (2023). A Critical Analysis of the Evidence for the SARS-CoV-2 Origin Hypotheses. Journal of Virology, 97. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00365-23

- Thakur, N., Das, S., Kumar, S., Maurya, V., Dhama, K., Pawęska, J., Abdel-Moneim, A., Jain, A., Tripathi, A., Puri, B., & Saxena, S. (2022). Tracing the origin of Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2): A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Journal of Medical Virology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28060

- Hao, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, M., Zhou, L., Shi, J., Cao, J., & Wang, D. (2022). The origins of COVID‐19 pandemic: A brief overview. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14732

- Coccia, M. (2022). Meta-analysis to explain unknown causes of the origins of SARS-COV-2. Environmental Research, 211, 113062 – 113062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113062

- Sallard, E., Halloy, J., Casane, D., Decroly, E., & Van Helden, J. (2021). Tracing the origins of SARS-COV-2 in coronavirus phylogenies: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 19, 769 – 785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01151-1

- Borsetti, A., Scarpa, F., Maruotti, A., Divino, F., Ceccarelli, G., Giovanetti, M., & Ciccozzi, M. (2021). The unresolved question on COVID‐19 virus origin: The three cards game?. Journal of Medical Virology, 94, 1257 – 1260. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27519

- Holmes, E., Goldstein, S., Rasmussen, A., Robertson, D., Crits-Christoph, A., Wertheim, J., Anthony, S., Barclay, W., Boni, M., Doherty, P., Farrar, J., Geoghegan, J., Jiang, X., Leibowitz, J., Neil, S., Skern, T., Weiss, S., Worobey, M., Andersen, K., Garry, R., & Rambaut, A. (2021). The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review. Cell, 184, 4848 – 4856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017

- Balaram, P. (2021). Natural and Unnatural History of The Coronavirus: The Uncertain Path to The Pandemic. Current Science. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v120/i12/1820-1826

- Lytras, S., Hughes, J., Martin, D., De Klerk, A., Lourens, R., Pond, S., Xia, W., Jiang, X., & Robertson, D. (2021). Exploring the Natural Origins of SARS-CoV-2 in the Light of Recombination. Genome Biology and Evolution, 14. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evac018

- Maxmen, A., & Mallapaty, S. (2021). The COVID lab-leak hypothesis: what scientists do and don’t know. Nature, 594, 313 – 315. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01529-3

- Ruiz-Medina, B., Varela‐Ramirez, A., Kirken, R., & Robles-Escajeda, E. (2021). The SARS‐CoV‐2 origin dilemma: Zoonotic transfer or laboratory leak?. Bioessays, 44. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202100189

- Domingo, J. (2021). What we know and what we need to know about the origin of SARS-CoV-2. Environmental Research, 200, 111785 – 111785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111785

- Tyshkovskiy, A., & Panchin, A. (2021). There is no evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 laboratory origin: Response to Segreto and Deigin (DOI: 10.1002/bies.202000240). Bioessays, 43. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202000325

- Andersen, K., Andersen, K., Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W., Holmes, E., & Garry, R. (2020). The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine, 26, 450 – 452. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9

- Zhou, H., Chen, X., Hu, T., Li, J., Song, H., Liu, Y., Wang, P., Liu, D., Yang, J., Holmes, E., Hughes, A., Bi, Y., & Shi, W. (2020). A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein. Current Biology, 30, 2196 – 2203.e3.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023

この論文を自然発生説の根拠とすることに対する批判的解説(Gemini):この論文は「S1/S2境界における挿入」という現象の一般論を示すに留まり、SARS-CoV-2が持つ極めて特異的かつ機能的な「設計」を何ら説明できていない。新規に同定されたウイルスRmYN02に見られる挿入配列「PAA」は、フリンによる切断に必須の塩基性アミノ酸(アルギニン:R)を欠いているため「フリン切断部位(FCS)」としては機能せず、これをもって感染力を劇的に高める「PRRA」という完璧な機能配列が自然界で発生した証拠とするには論理的な飛躍が大きすぎる。さらに、SARS-CoV-2のFCSには、近縁の野生ウイルスでは極めて稀で、ヒト細胞での発現最適化を目指す遺伝子操作に多用される「CGG-CGG」という不自然なコドンが使われており、RmYN02のような自然サンプルの存在はこの「操作の痕跡」を否定する根拠にはなり得ない。

この論文を自然発生説の根拠とすることに対する批判的解説(Gemini):この論文は「S1/S2境界における挿入」という現象の一般論を示すに留まり、SARS-CoV-2が持つ極めて特異的かつ機能的な「設計」を何ら説明できていない。新規に同定されたウイルスRmYN02に見られる挿入配列「PAA」は、フリンによる切断に必須の塩基性アミノ酸(アルギニン:R)を欠いているため「フリン切断部位(FCS)」としては機能せず、これをもって感染力を劇的に高める「PRRA」という完璧な機能配列が自然界で発生した証拠とするには論理的な飛躍が大きすぎる。さらに、SARS-CoV-2のFCSには、近縁の野生ウイルスでは極めて稀で、ヒト細胞での発現最適化を目指す遺伝子操作に多用される「CGG-CGG」という不自然なコドンが使われており、RmYN02のような自然サンプルの存在はこの「操作の痕跡」を否定する根拠にはなり得ない。 - Zhang, T., Wu, Q., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak. Current Biology, 30, 1346 – 1351.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022

- Li, X., Zai, J., Zhao, Q., Nie, Q., Li, Y., Foley, B., & Chaillon, A. (2020). Evolutionary history, potential intermediate animal host, and cross‐species analyses of SARS‐CoV‐2. Journal of Medical Virology, 92, 602 – 611. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25731